Commercial aviation is currently responsible for around 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This is set to triple in the next 30 years. And while Covid-19 may have given the skies temporary respite, with many of us eager to board a plane as soon as is possible, reducing harmful emissions by reducing air travel is about as likely as Nancy Pelosi backing a 2024 Trump presidential bid.

But we are already on the right track. The global aviation industry is working towards increased fuel efficiency and with 110 countries committing to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, aerospace manufacturers are racing to develop sustainable technologies that support zero-emission flight.

Boeing intend to deliver aircraft capable of flying on 100% biofuels (derived from living materials) by 2030, and Airbus are working to develop the world’s first zero-emission commercial aircraft by 2035. These targets are ambitious but given that commercial jets have an average lifespan of 20-25 years, the large aircraft delivered in a decade’s time will still be flying by 2050 and need to be able to uphold the world’s 2050 targets.

This challenge also belongs to the general aviation manufacturers and it’s spurring on suppliers, such as CAV, to innovate parts and systems that further lighten the energy and environmental load of aircraft.

The lighter an aircraft, the more energy efficient systems are, or the less drag there is, the less fuel it requires. Add to that the use of sustainable alternatives to kerosene and petroleum fuels, or the use of a different power source altogether, and some serious reductions to carbon emissions can be made.

SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUELS

Rather than burning fossil fuels, many airlines are now beginning to blend traditional aviation fuel with sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) derived from bio-based materials such as feedstock or organic waste. Because they combust in a comparable way to fossil fuel, SAFs must comply with strict criteria that ensures carbon is reduced across their lifecycle as part of their production process.

Currently the use of blended SAF is restricted internationally to 50%. For a larger percentage to be used, or for an aircraft to run solely on SAF, significant modifications would need to be made to aircraft and engine designs and certification to meet required safety and efficiency criteria.

ELECTRIC AIRCRAFT

Electricity generation and the subsequent use of that electricity as a power source is far more efficient than the burning of fuel and releases less carbon dioxide over its lifetime; particularly if that electricity is generated from renewable sources such as wind or solar.

The introduction of a fully electric, rechargeable aircraft that eliminates the need to burn fuel seems ideal, but battery technology only affords a limited amount of energy to be stored, and this limits the range of an aircraft. No one wants to fall out of the sky halfway to their destination because the battery doesn’t have enough juice! It would also mean a long stop at the airport to charge, before it could take off again.

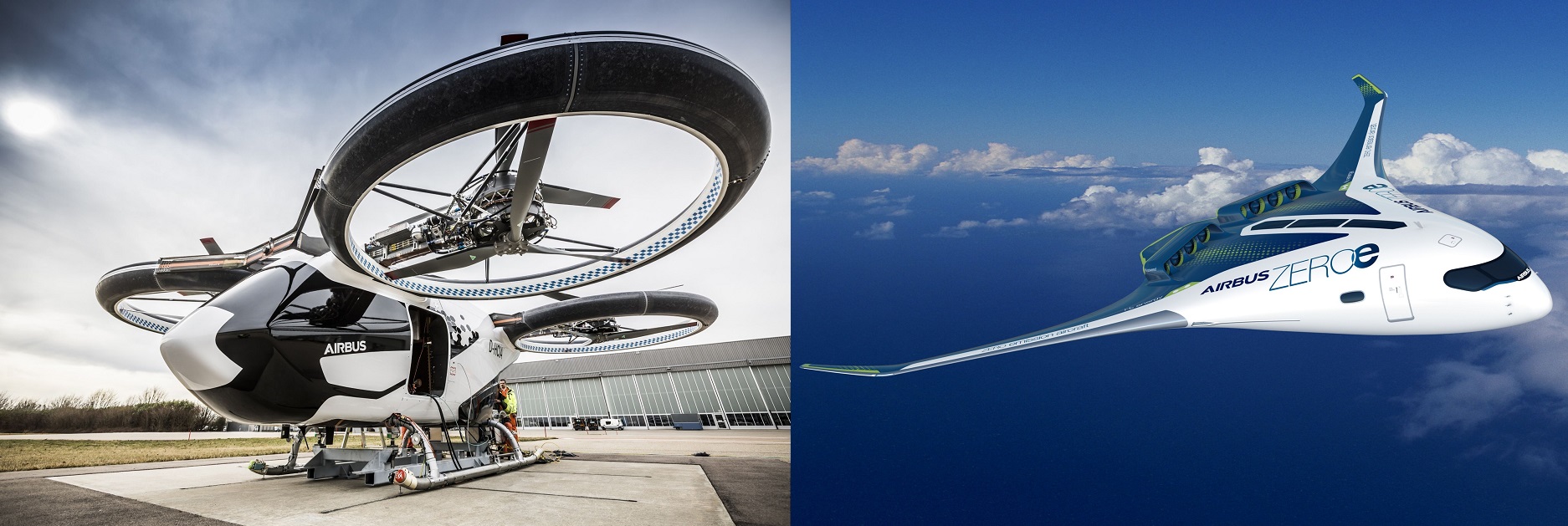

Electric aircraft may however soon have a place in our cities. Addressing the twin problem of pollution and congestion, unmanned automated electric vehicles could be used to transport passengers or cargo short distances.

Taking off vertically, such vehicles could easily be designated take off space and charging points within cities, even on the rooftops. Acting as taxis and couriers, with journeys between 15 and 250km, the limitations of battery power on flight range all but disappears.

HYDROGEN

Hydrogen can be produced without greenhouse emissions by using renewable energy sources, and given that it only produces water when burned, it offers a virtual panacea for air travel.

Airbus’ development of a zero-emission commercial aircraft relies on hydrogen as its primary power source. But before you envisage a repeat of the Hindenburg, rather than floating about in large pockets as a gas inside the aircraft, the hydrogen would be stored safely as either a liquid or as a part of a fuel cell.

Boeing has already created some small aircraft powered by hydrogen, but the added container weight and space required for storage means that new commercial aircraft must be carefully tailored in other areas to reduce weight and subsequent drag. Not to mention that airports must look to build the infrastructure required to deliver hydrogen to their planes.

WHERE CAV FITS IN

Regardless of which solution powers our next flight, before it takes off, work is needed to improve aircraft design and system efficiency.

CAV’s drag reduction technology is essential for increasing fuel efficiency and can already be found on commercial airliners. It reduces drag by up to 20% and saves a typical widebody airliner around 1000 tonnes CO2 per year.

There are also many developments underway to innovate TKS Ice Protection for these new power solutions. Lighter weight components, reduction in TKS fluid requirements for shorter journeys, and the hybridization of TKS with electric anti-icing, is enabling us to optimize TKS for both electric and hydrogen powered aircraft, as well as providing additional gains to existing designs.

Furthermore, CAV’s ability to analyze aerodynamic data and our unique laser drilling capabilities enable us to devise drag reduction, ice protection and other panel-based solutions bespoke to each new individual aircraft.

As the major aircraft manufacturers race against the carbon clock, we are handing them the tools necessary to complete their mission.